[completed 2005-02-16]

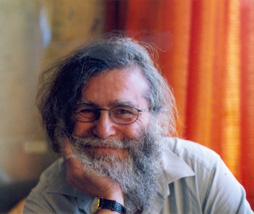

[completed 2005-02-16] Robin Fairbairns maintains the TeX FAQ and the UK CTAN node. He is also a member of the LaTeX Project team.

[completed 2005-02-16]

[completed 2005-02-16]

Robin Fairbairns maintains the TeX

FAQ and the UK CTAN node. He is also a

member of the LaTeX Project

team.

Dave Walden, interviewer: Please tell me a bit about your personal history independent of TeX.

Robin Fairbairns, interviewee: I came up to Cambridge University to read Natural Sciences, but changed early on to read Mathematics. I then took a graduate Diploma in Computer Science: you could only study computer science as a graduate in Cambridge in those days. I then took jobs in the Cambridge Language Research Unit; back at the Mathematical Laboratory (where I had studied for the Diploma); and then as one of the second wave of employees at a startup company which made computer graphics equipment. Seventeen years later, in 1992, I was “downsized” from the company, and once again found myself working at the Computer Laboratory (which had dropped the “Mathematical” part of its title in the 1970s).

DW: When and how did you first get involved with TeX and its friends?

RF: The company I worked for was a DEC OEM, and DEC used sometimes to send us fliers for Digital Press books. I persuaded the company to buy Knuth's first TeX and Metafont book (ostensibly for the software department's library). I was deeply impressed, but knew that it wasn't for us, since we had no better printer than a secretary's daisywheel used occasionally to print documentation for customers. Then things changed: I was asked to “evaluate” laser printers for the company to use, in place of those commandeered daisywheels, and spent a short happy period programming printers' PostScript engines, hacking at a freeware Digital Runoff-replacement, and so on. In the end, the company chose a DEC LN03 printer, and it wasn't long before I realised I could make TeX work on it. There was the slight embarrassment of persuading the higher management to enhance the brand-new printer to work with TeX, but apart from that, I was on my way!

DW: Practically daily I see your answers to queries on the comp.text.tex and TeXhax lists. How did you come to be a contributor to the TeX community?

RF: Once I became a TeX user, I wanted to read more about it. I found TeXhax, UK-TeX and various other online newsletters; I found the Aston archive (which I accessed via a 9600-baud X.25 network connection), and I was “on the learning curve”. I read the LaTeX manual, and was impressed with Lamport's thinking (and back then, Lamport used still to post to TeXhax). Eventually, I realised I knew enough to start answering questions. So I did: it seemed the right thing to do.

I attended the inaugural meeting of the UK TeX Users' Group, and was impressed by all these people who had been running the archive and were now forming the committee of the new group. Then, when I got back to work at the University, Phil Taylor persuaded me that I should join the committee myself.

In fact, I joined the UK-TUG committee as it approached the apogee of its activity. Sebastian Rahtz edited several issues of the group's magazine Baskerville, and Jonathan Fine and I got it printed and distributed. The group decided to start working on a FAQ to replace the one by Bobby Bodenheimer, which had been decaying somewhat: I volunteered to produce it, and by December 1994 we had “answered” 100 questions in a special edition of Baskerville.

At this time, Sebastian was running the Aston archive as the UK CTAN. When Aston University's new director of computing decided he wanted to shut the archive down, the frantic search for a replacement found only one candidate host: my department. So, after not very long, I was taking over CTAN work from Sebastian, thus freeing him for work on TeX Live.

TeX Live was (I think) the last great effort of those glory days of UK-TUG; it was an exciting time, but I'm not sure I could keep up the pace. I served as chairman of the committee for a while, but am no longer at all active in UK-TUG. I shall, however, be forever grateful to UK-TUG for enabling me to commission a cake from a local cake shop … with a Bibby cartoon on it: I knew it was a good cake shop, but this cake was a work of art!

DW: May we return to the FAQ for a minute? You stopped with your description of the 100 questions in a special edition of Baskerville, but that wasn't the end of it — you still maintain the FAQ.

RF: Actually, those first 100 questions contained a cheat, which Jonathan and I cooked up just before printing, in order to give us a nice round number (I would maintain that it didn't mislead, since it merely speculated about the future …). As I remember, all but a couple of the answers in that first issue were written by members of the UK-TUG committee.

After we had distributed a printed copy to our members, the committee decided that we should make the FAQ available via the Web. This was a pretty radical step, at the time: the FAQ had originally been printed and distributed as a benefit of membership of UK-TUG. So Alan Jeffrey wrote a CGI script, and provided a site at the University of Sussex. Alan's script is still the engine through which the FAQ appears on the Web, but the site migrated to Cambridge long ago.

Other than the help from Alan, I've been mostly on my own since that first release: which is to say that I write FAQ answers, I edit things that people contribute, and I maintain Alan's script. But if people didn't “believe in” the FAQ, to the extent of making suggestions (or sending actual answers), I could never keep it up.

But I have kept it up: there are 375 answers in the current release, and there's also a long list of subjects for potential new answers… just waiting for me to find some spare time!

DW: The world wide TeX infrastructure is very extensive. Please tell me your thoughts on the evolution of this community and how it does its work.

RF: I wasn't around to observe the early “glory days” — the days during which the world was starting to realise that TeX was here to stay, and worth devoting effort to.

What I most definitely recognise, in retrospect, is step changes in the development of the TeX community; and I think the birth of the newsgroup comp.text.tex was one of those. The newsgroup quickly took over the support rōle of TeXhax, and has attracted a group of supporters which has proved remarkably stable over the years. I suppose it's reasonable to say that much of my work has developed as a result of comp.text.tex.

One other, particularly valuable, change has been the recognition that TeX can provide hypertext. Hypertext was a neglected area of research until it was popularised by Berners-Lee, but now it's almost a sine qua non of technical document preparation.

The TeX community seems to me to function best when very small groups are doing the work. Examples would be Hàn Thế Thành (who had external advisors when working on his Ph.D., but seems to have done most of the pdfTeX work on his own), and the (almost) one-man-bands that produce distributions like Web2C, teTeX and MiKTeX.

By contrast, I have a strong suspicion that large TeX projects tend to run slowly. We may even be seeing this effect with the TeX Live team, which seems to be finding it increasingly difficult to meet deadlines for release of their excellent product. Far worse was the NTS project which, with its carefully devised committee structure and formal project reviews, delivered even its first product (eTeX) spectacularly late by comparison with the timetable everyone outside the project expected. The end result of such delays is that the product's impact was lessened, even though it offered things that the world actually needed.

The weakness of the community's distributed structure is its dependence on particular people. There was, for example, a real concern when Hàn Thế Thành finished his Ph.D. — who was going to continue the work? That one has turned out well (Thành himself has managed to stay active), but the potential for disruption is always present.

DW: Do you have thoughts on where the TeX community is going?

RF: I believe that the crucial next step for the TeX community should be to embrace multi-lingual typesetting. We have a limited model of multilingual work, in what babel (and a number of similar packages) do, but there are fundamental limitations to what we can do with that sort of approach.

The aim, in my mind, is to make the typesetting engine switch as seamlessly from one language to another, as does TeX between text and mathematics. TeX itself just can't hope to do this: its limitations on the size and organisation of fonts, alone, make it an undesirable engine to use, even if the character encoding issues could be resolved.

Nearly 10 years ago (I think it was), I was enthused by a presentation at CERN about Omega. Omega could in principle be a vehicle for this multilingual future (cf. Javier Bezos' experimental mem package). However, Omega's development base seems distinctly precarious, and no-one claims that it's currently “finished”; I really can't guess where it's likely to go from here.

DW: Your contributions to the highly technical TeX community are manifest. However, I see technological progress as being driven by people who have lives outside of technology. Will you say a few more words about your personal life?

RF: I work as a system administrator at the Cambridge University Computer Laboratory; while I do have responsibility for TeX support within the department, it's officially a minor part of my work.

I'm married (second time) to a musician; she and I are rather self-indulgent about our collection of recorded music, and I also collect old guide books (mostly to the UK and, to a lesser extent, the rest of Europe). We each have a pair of grown-up children; only one of them (my son) lives in Cambridge.

DW: Thank you for taking the time to participate in this interview. I've admired your posts to the various TeX lists and sometimes thought, “Who is this guy, and how did he get to know so much about TeX?” Now I think I have a glimmer of understanding.